“Necessity is the mother of invention,” says Oded Distel, director of Israel NEWTech (Novel Efficient Water Technologies). When it comes to Israel’s water supply, he’s dead-on. The country that brought modern drip irrigation to the global market continues to innovate, making the best of its water scarcity issues and introducing those homegrown solutions to the world. In fact, Booky Oren, chair of the upcoming WATEC 2009 Conference, tells us that Israel is the “global Silicon Valley” for water technology solutions.

After day one of our press tour, we were suitably impressed. We’d spent most of our day in Jerusalem visiting Hagihon, the water and wastewater works corporation, talking with representatives from companies with impressive and varied new technologies, including A.R.I.’s unmeasured flow reducer device, Tahal Group’s real-time modelling for water contamination and security, and TaKaDu’s smart network for monitoring water loss reduction.

The implementation and success of these new technologies is in large part due to Israel’s social climate, which allows for unique partnerships between academies, industry, government and what Distel calls a “seasoned” community of venture capital funds. And the country’s small size doesn’t hurt, either. Its informal, open atmosphere and well-connected networks make it easier for Israeli upstarts to burgeon and quickly enter the global market.

Even so, there are some drawbacks. “Israel is a candy store for technologies, but we are lacking the financing to make the technologies into companies,” says Avi Broder, CEO of BDB Technologies & Hi Tech Investments Ltd. BDB is a relatively young company that is actively seeking to invest in technologies right out of academic institutions. “Israel is generating some great ideas in desalination, water treatment, water security and safety,” says Broder. “Cleantech is where we have our foot on the pedal.”

Canadian scientist Brian Berkowitz, the head of chemical research support at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science, says that Israel’s investment climate is an important part of the development process. Berkowitz has worked in water remediation, including studying how contaminants move in groundwater systems, and is taking part in the commercialization of two technologies. “Incubators are used for seed money to do a prototype and fund the testing to prove it works,” he says. “Then we look to private investment.”

Unfortunately, Broder says, venture capital is not playing in the early stages. Broder and BDB have been looking to Canada as a gateway to the international market. “Canada today has a very interesting source of investments,” says Broder, who saw Vancouver’s GLOBE 2008 as an opportunity to explore those opportunities.

Canada and Israel

Several avenues exist that support Canadian-Israeli partnerships. Our countries share a free trade agreement (CIFTA), and there’s the Canada Israel Industrial Research and Development Foundation (CIIRDF), which funds Canadian and Israeli companies joint R&D projects. “Through funding, there an be a sharing of experts,” says Catherine Gosselin, a Canadian trade commissioner to Israel. “We continue to support import-export, but we’re also trying to foster relationships between researchers and companies.”

Beyond these initiatives, Canadian investment companies are showing interest in Israeli water technologies. Kinrot Technology Ventures, Israel’s leading seed investor in water and clean technologies, was privatized in 2006 by Vancouver’s Stern Group in cooperation with the Israeli chief scientist’s offices. Kinrot subsidizes 24 incubators and has approximately 200 projects in the development stage at any given time in several areas, including telecommunications and medical.

The interest goes both ways. “Canadian products are very well-perceived here in Israel,” says Gosselin. “One company that’s been very successful, for instance, is Zenon—they were one of the first success stories for Canadian companies here in Israel.” In 2004 and 2005, Zenon and Mekorot, Israel’s national water company, received funding from CIIDRF to work together on the development of new ultrafiltration membranes for seawater desalination and purification.

More recently, Clear Flow Consulting Inc., a Canadian company that develops wastewater and erosion control technology to improve water quality, received a National Research Council of Canada grant of $125,000 to install a pilot project at the Nablus River in Israel. The project is based on wastewater and aquaculture wastewater (release water from fish farms that’s high in ammonia, nitrates and nitrites), and, since installation, Clear Flow’s products have been able to reduce these levels dramatically. “Israel is open to many avenues in water treatment that will help develop their water management,” says Jerry Hanna, Clear Flow’s president.

Integration

Israel’s research into a variety of technologies and solutions is part of its multi-faceted approach to water treatment. “There’s no one solution,” said Doron Sapir, deputy mayor of Tel Aviv, as we convened in the municipality’s bright, welcoming Center for Environmental Education. “They’re all integrated.”

After five consecutive dry winters, the country’s main freshwater source, Lake Tiberias (also known as Lake Kinneret and the Sea of Galilee, and which is fed by the River Tiberias, in turn fed by the River Jordan and several other small streams from the Golan Heights), is at a dangerously low level. According to water authority data, only 80-85 per cent of the average annual rainfall was recorded in 2009 in the Lake Tiberias area. In January, the lake’s water level fell to a record low— only 0.34 metres above the level at which pumping must be stopped.

Israel’s agriculture and finance ministries formally declared a drought in large parts of the south on June 2, and, on July 1, right in the middle of our tour, the Water Authority’s new levy on surplus household water consumption came into effect. The purpose of the tax is to make individuals aware of how much water they use, and how they can use it more wisely.

Even after implementing such measures, Israel has been forced to look elsewhere for freshwater. Alternate sources include groundwater aquifers and spring water from Northern Israel and the most recent addition to the mix, Israel’s mammoth desalination operations, which create 115 million cubic metres of freshwater per year (or 330,000 cubic metres per day).

As we entered the desalination plant at Ashkelon, the sheer magnitude of the place accomplished the impossible: 35 journalists were silenced, awestruck. “Hurricane Katrina was an example of when nature took over mankind,” Assaf Barnea, Kinrot’s CEO, told us the previous day. “Here is where mankind took over nature.”

According to the Ministry of Environmental Protection, the State of Israel is taking steps to significantly increase seawater desalination, at a scope that could reach some 600 million cubic metres per year by 2013—a quantity equal to about half of the freshwater which is pumped in Israel on average each year—making desalination the country’s main source.

But while it does provide a solution for a major problem, desalination has some drawbacks. For one, the process is incredibly energy-intensive. Secondly, at the end of the line, only 33 per cent of the seawater intake ends up as freshwater. The remaining two-thirds are returned to the sea as concentrated brine—the effects of which are not yet known, though they are being studied.

In instances such as these, investors like Kinrot and BDB are important in increasing efficiencies and working toward sustainability. As problems arise, new solutions are being developed all the time. For instance, Kinrot has invested in a company called SeaTech Innovations Ltd., which is developing a way to produce high value chemicals from leftovers emitted from desalination plants. The process is based on multistage controlled sedimentation, which produces different chemical compounds such as magnesium carbonate, strontium carbonate and calcium carbonate in each stage. This process may dramatically enhance the return on investment in desalination plants, and may help them to be compatible with the developing regulation trend of Zero Liquid Discharge.

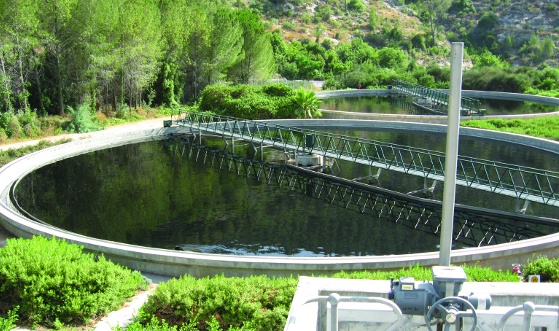

Even prior to desalination advancements, good water management has been firmly established as part of the Israeli lifestyle. Since the 1970s, the country has aggressively pursued wastewater reclamation for irrigation, reaching a 75 per cent recycling rate, which is by far the best in the world (Spain is number two at 12 per cent). Combined with drip irrigation technology, the country has the highest ratio in the world of crop yield per water unit. Several smaller communities use onsite treatment solutions, such as EPC’s low-energy Bio-Disk, to treat and prepare wastewater for reuse. “We have enough water during this drought because we reuse a lot of it,” says Oren.

At the end of three days, we left the tour astounded by Israel’s proactive, entrepreneurial spirit. If this country with scarce and limited resources can achieve sustainability through integrated management, we thought, there’s something to be learned. Water-rich countries like Canada shouldn’t wait for a crisis—we should take advantage of the excellent opportunity to learn from Israel’s experience, and work together to continue to find and share solutions.

With thanks to Israel’s Ministry of Industry, Trade and Labour, Israel NEWTech, Sharon Cohen, Jonathan Levy, Vladimir Banic, Noam Moshenberg, Gilad and Irit.