On the surface, the grate is inconspicuous— it doesn’t appear to be any different than all the other sewer grates in the city of Toronto. The area where it’s located is mostly devoid of foot traffic, save for a few people walking around in fluorescent safety vests and hard hats.

It is quiet and unremarkable—on the surface.

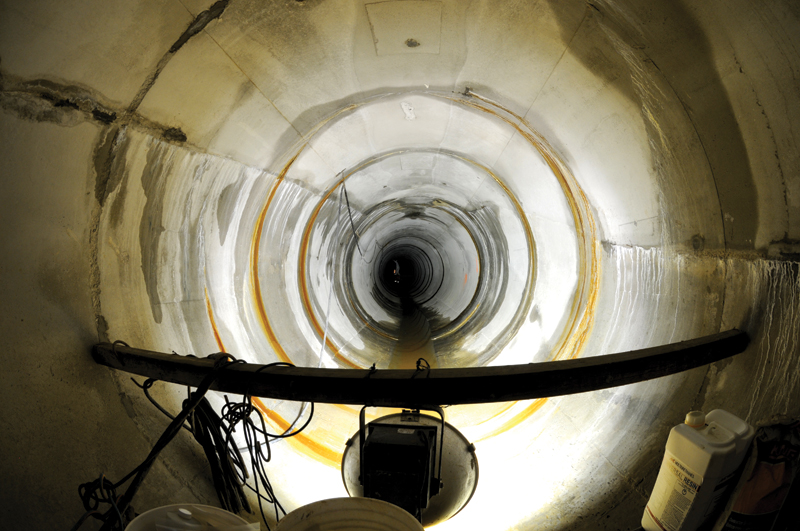

But below the surface is a labyrinth of tunnels and shafts, and the largest oil-grit separator of its kind in Canada. Located in the West Don Lands community, which has been characterized as “Toronto’s next great neighbourhood,” the West Don Lands stormwater quality facility and outfall is an impressive and innovative management system.

Currently consisting of three tunnels and one main shaft, the facility has been in the works since 2007. It services the West Don Lands community and any future development in the North Keating portion of the Lower Don Lands. The West Don Lands, an 80-acre site spanning from Parliament Street to the Don River and King Street to the rail corridor, is also home to the 35-acre Athletes’ Village for the 2015 Pan/Parapan American Games. The area is located within the floodplain of the Don River, which means flood mitigation was a key consideration in its development.

In 2007, the Ontario Realty Corp., which has since merged with infrastructure Ontario, began work on behalf of Waterfront Toronto to construct the area’s massive flood protection landform, one that took more than $120 million and about 40,000 dump trucks worth of soil to build. It protects not only the West Don Lands, but a 210-hectare area, including Toronto’s financial district, from flooding.

“This required the entire site to be regraded to drain away from the river, which required a new storm outfall to be installed,” said Peter Langan, professional engineer and project manager of the facility as a principal at R.V. Anderson. “The new outfall is located along Cherry Street, leading to the Keating Channel.”

Construction of the project commenced in May 2011 and the tunnels and shaft were completed in May 2012. The treatment building is the next phase of the project and will start in 2014 with completion expected in time for the games in summer 2015. The tunnels and shaft cost approximately $20 million, and the treatment building is estimated to be $10 million. The facility is part of Waterfront Toronto’s $30-billion revitalization project.

As it stands, the treatment facility’s main shaft is 25 metres deep and can store approximately 3,000 cubic metres of water. The concrete-lined tunnels are three metres in diameter, 350 metres long, and 25 metres deep. These tunnels were constructed deep in bedrock using a tunnel-boring machine.

“The main shaft will store stormwater so that we can pump it to the treatment system at a slower rate. The main shaft is like a shock absorber,” Langan said. “It takes in all that rush of stormwater, and then we hold it there and we pump it at a slower rate to the treatment equipment. That allows us to use smaller, more economical treatment equipment.”

The facility was designed with larger rainfall events in mind and is able to convey and manage very large storms to ensure the area is not impacted by heavy rainfall events, like the 2013 Toronto flood. The facility has a treatment rate of 750 litres per second and a peak flow rate of about four-and-a-half cubic metres per second.

Once the treatment building is constructed and completed, stormwater will be conveyed through treatment equipment normally used in the water and wastewater industry. Langan said the implementation of this fully integrated stormwater management system to treat stormwater to a very high level will be the first of its kind in Canada.

“There are very few municipalities that have adopted rigorous stormwater management criteria like the City of Toronto with its Wet Weather Flow Management Plan guidelines,” he said. “Under these guidelines, this stormwater management system incorporates three aspects: source water controls, conveyance controls, and end-of-pipe controls.”

The first step in treatment is the oil-grit separator, which treats a large drainage area of more than 30 hectares. The flow will then be conveyed into storage where it will be pumped into the treatment building for further treatment: fine screening and a ballasted flocculation clarifier. UV disinfection will be the final stage in treatment before the water is discharged to Keating Channel.

“Let’s get it as clean as we can before we put it into the lake,” Langan said. “The city is endeavouring to improve the quality of the discharges to Lake Ontario, and this project demonstrates how to achieve a high level of treatment for stormwater.”

Langan said the West Don Lands facility will be the start of a “real, tangible effort for environmental protection” regarding stormwater releases.

“The Greater Toronto Area has a huge drainage area going into Lake Ontario, and there are very few sites that are treated to this high level of quality. It’s an incremental improvement,” he said. “But you have to start somewhere. You have to do those little increments whenever you can, and it’s when all these increments add up, 20 years down the road, you can see you’ve made a big difference.” WC

Rachel Phan is Water Canada’s managing editor. This article appears in Water Canada’s March/Aprl 2014 issue.