Community wastewater treatment plants and botanical gardens generally don’t have all that much in common. One is a noisy industrial facility while the other is an appealing community gathering place. A nearly completed wastewater facility in the District of Sechelt, British Columbia, located on the lower Sunshine Coast, will blur the line between the two.

The facility will utilize a fed batch reactor (FBR) solution by Organica, a Budapest-based water treatment provider. The process incorporates natural plant roots as a biofilm carrier to improve treatment efficiency and oxygen transfer characteristics. It combines traditional treatment technologies with natural, locally sourced vegetation in a greenhouse setting. Although in use at 30 to 40 sites abroad, Sechelt is set to become the first location in North America to utilize Organica’s innovative technology. (Ed. Note: For more information on the Sechelt facility, now known as the Sechelt Water Resource Centre, click here.)

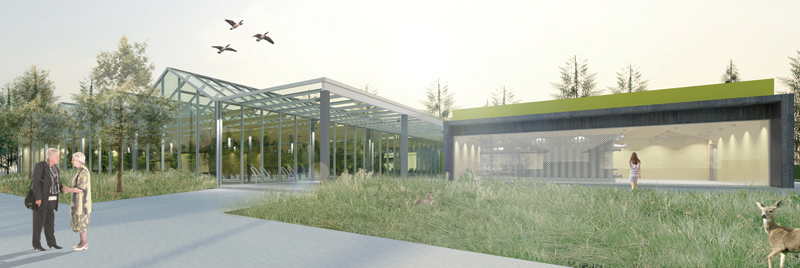

Sechelt’s new treatment plant in the community’s core will bear little resemblance to the facility that had occupied the same spot for 35 years. It will include a greenhouse, an on-site learning centre and learning material, a meeting area, and a covered walkway. The facility will also be open for tours, and perhaps most importantly, it will be entirely noiseless and odourless.

Work on the $21.3-million project, which will be built to LEED certification, is being completed by Maple Reinders Inc., a consortium including Urban Systems Ltd., Technologies Canada, and Veolia Water Solutions. Veolia is supplying the technology that will make the plant possible.

“You have a wastewater treatment plant that doesn’t look like a wastewater treatment plant,” says Don Holland, VP of business development and infrastructure at Maple Reinders. “They wanted it to be more than just a wastewater treatment plant. So that’s kind of why they picked us, because it’s almost like a botanical garden.”

The technology is particularly valuable given the plant’s location in a residential area. When the district’s old Ebbtide wastewater treatment plant was built 35 years ago, the site was chosen because it was outside the village limits and at an extremely low elevation—about sea level. Today, the site is bordered on three sides by private residences. Although the district considered building the replacement facility at a more secluded location, a pumping station would still be necessary at the current site. As a result, the district began exploring ways to build a new facility on the original site, which would blend into downtown Sechelt and limit disruptions to neighbours.

“[We] made it very clear to the industry that we were committed to being innovative, that we wanted the proponents to stretch themselves in their approach,” says Sechelt mayor John Henderson. “We told them the criteria we’d use to evaluate their submissions were things like it had to be noiseless, it had to be odourless, and higher marks for the more green the submission was.”

Not only will the new facility be substantially more appealing to the eyes and the nose, the quality of treated water will also be very high. “It will be treated to such a standard where we can use it for agriculture,” Henderson says. “Or it could be as basic as running a pipe across to the local baseball field, so we can water [it] in July, August, and September, when water’s a bit scarce. We expect certainly through the summer months to reuse a great percentage of our effluent.”

Henderson says he believes the town’s openness to innovation has allowed it to find an ideal fit.

“For a small community like Sechelt, our willingness to embrace innovation, and indeed put it at the core of what we wanted the industry to supply us with, really gave industry the challenge to come up with something that was innovative, that was creative, and as a result is something that we’re going to be very happy with,” he says.

Holland agrees: “One of the most interesting things is that the district went out on a limb for this project. […] They wanted it to be a valued asset to the community—it’s not something that’s going to be put away in the corner. They wanted something that they could take pride in and show that they are doing the right thing.”

In fact, the town has already received visitors from other communities interested in Sechelt’s new approach to water management in a downtown setting. “We’ve already had a few visitors for that purpose,” Henderson says. “I would encourage anybody in a decision-making role like mine to not be afraid of demanding that the industry get innovative.” WC

Clark Kingsbury is Water Canada’s assistant editor. This article appears in Water Canada’s May/June 2014 issue.