People living in the North are observing changes in the environment. They have questions about the health of northern ecosystems due to the effects of upstream development and climate pressures and a desire for increased environmental monitoring. Since 2010, indigenous groups in the Northwest Territories’ Slave River Basin have been involved in a partnership called the Slave River and Delta Partnership (SRDP)—a collaboration among government, local people, and educational and academic partners to monitor the northern ecosystem and support water stewardship.

The SRDP emerged to tackle concerns like fish deformities and taste, altered river flows, and changing ice conditions. In the past, some of these concerns were examined by researchers using Western science practices. Researchers took that data back to their labs away from the local communities for further assessment. This so-called “helicopter” approach has often been applied in indigenous communities and has created mistrust of scientific researchers because it gives little opportunity for community involvement.

Indigenous communities are committed to their own ways of knowing about the land and water. They have traditions of storytelling using symbols and face-to-face learning. This knowledge forms the basis of their resource-management decisions and wellness. There is much debate on how to bridge these different ways of knowing about the world, both practically (how do we blend narratives with quantified measurements of phenomena?) and theoretically (what actually counts as knowledge?).

Six faces of knowledge

Between 2012 and 2015, the SRDP along with partners from the University of Saskatchewan received funding from the Canadian Water Network to explore community concerns about the Slave River and Delta. The Slave Watershed Environmental Effects Program (SWEEP) aimed to address three questions:

- Is the water safe to drink?

- Are the fish and wildlife safe to eat?

- Is the ecosystem healthy?

Community members and research partners met frequently to design the research program, decide on priorities, and figure out how to blend traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) with scientific methods to help answer these questions. A guiding framework that recognized parallels between traditional knowledge systems and common phases of scientific exploration was developed.

The Six Faces of TEK developed by Nicolas Houde at the Université du Québec à Montréal resonated with the partnership and the research team. The six interconnected faces were aligned with an eight-phase model for conducting community-based research as experienced while undertaking the project. The project evolved, it also adapted to respond to the needs of the communities. For example, the SWEEP team produced a video instead of a document to share results when elders indicated their preference for non-written formats. There was a clear parallel between observations made by indigenous people in their daily lives and how these observations inform decisions about resource use and the methods used by researchers to observe and measure environmental changes (collecting and analyzing samples against past and present-day standards).

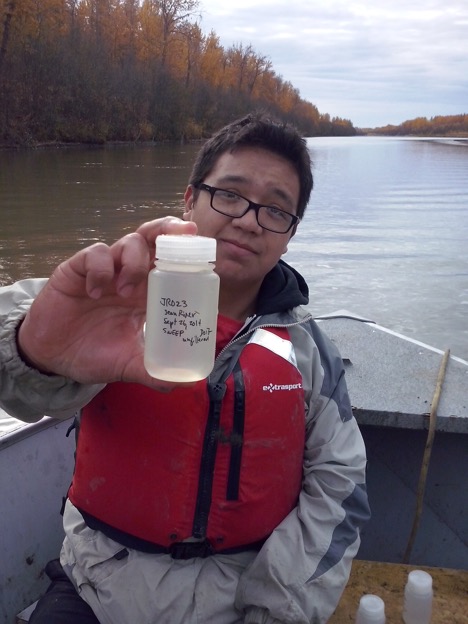

Elders and local people were interviewed. They also shared their knowledge informally while walking on the land with the researchers to various sites. Local people were also trained to collect data using technical instruments for scientific measurement of different indicators. By drawing on each other’s methods for acquiring knowledge, both groups benefitted in understanding the pressures on traditional lifestyles and ecosystems. By bridging these two modes of learning and simultaneously studying scientific and traditional indicators of the health in the area, those involved in SWEEP were able to come to a more complete understanding of the impacts on the river and delta.

There is a clear demand for new ways of exploring environmental and sustainability problems that bridge different knowledge systems and enhance participation of citizens among researchers, funding agencies, and related organizations. The SWEEP project and its guiding framework provide one example of a means to ethically bridge knowledge systems, examine problems holistically, and support participation in water stewardship. For other practitioners in the field, it demonstrates it is possible to recognize the values of local and indigenous people and scientists as a step toward reconciliation.

Lalita Bharadwaj is an associate professor and Lori Bradford is a research associate in the School of Public Health with the University of Saskatchewan.