New research from the University College London suggests that current metrics used to determine the global water crisis might not accurately reflect scarcity and sufficiency.

The research, led by the UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources and UCL Geography, targets the evolution of methodologies over the last thirty years as inaccurate. The researchers point to the development of holistic measurements from threshold indicator, arguing that the threshold for water scarcity is context-specific and based on an industrialized country in a semi-arid region.

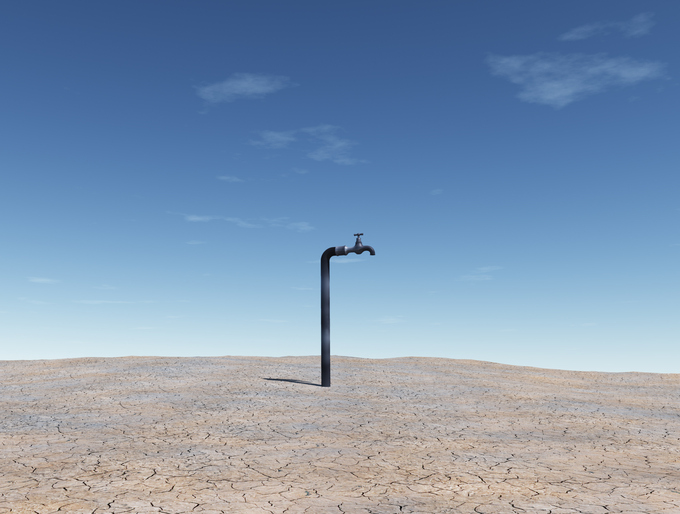

Courtesy, University College London, Damkjaer, and Taylor.

Other areas of weakness pointed out by the research are estimations of renewable freshwater using mean annual river runoff, which they say “masks hydrological variability.” The report also found that the

“misrepresentation of freshwater resources and demand is particularly severe in the low-income countries of the tropics where the consequences of water scarcity are projected to be most severe and where most of the global population now lives,” wrote Simon Damkjaer and Richard Taylor, the authors of the study.

Richard Taylor, UCL Geography professor and co-author of the paper, said, “How we understand water scarcity is strongly influenced by how we measure it. Grossly misrepresentative measures of water scarcity can identify scarcity where there is sufficiency and sufficiency where there is scarcity. An improved measure of water scarcity would help to ensure that limited resources are better targeted to address where and when water-scarce conditions are identified.”

The authors have called for a renewed debate on best practices in measuring water scarcity and argue for its redefinition based on three pillars:

- A physical redefinition of freshwater storage that addresses imbalances in intra- and inter-annual flux of supply and demand.

- A redefinition that accounts for different human environments, geographical and socio-economic.

- An incorporation of participatory decision-making processes that consider an array of freshwater storage possibilities: dams, renewable groundwater, soil water, and virtual water trading.

Such an approach, they contend, “would enable for the explicit consideration of groundwater, the world’s largest accessible store of freshwater which accounts for nearly 50 per cent of all freshwater withdrawals globally.”

The research, The measurement of water scarcity: Defining a meaningful indicator, can be found online.